The stats of ‘Russia 2018’ confirmed the absence of any meaningful correlation between physical efforts and football performances. The overall outcome is in line with the available literature, although more clearly than widely perceived, in our view. Our main takeaway is the confirmation of the validity of ball-based training sessions, key to master football. By the way, if you believe that Usain Bolt could simply leverage on his speed to dribble or score on counterattacks, jump to the last few charts of this analysis.

Not surprised by the outcome, but by its magnitude

Russia 2018 gave us the opportunity to assess, once again, if there were any correlation, in football, between a good physical performance and results. We run the analysis by looking at a number of regressions between our Athletic Performance Index (API, measuring the physical performance) and the Soccerment Performance Ratings (SPRs, which quantitatively measure the technical performance).

In line with what the available literature suggests, there is no evidence of any strong correlation.

Actually, there is zero correlation. We were expecting a slightly positive or slightly negative correlation (more running is needed while defending) and, instead, the ‘R-squared’ of the regression, when considering all roles, is 0.000.

This leads to a foregone, but anyway important consideration. In order to be a great footballer, it is simply not enough to be great athlete. Otherwise, Usain Bolt would win the Ballon d’Or (instead, it seems he will be soon sign for either Central Coast Mariners or for United Soccer League and not for Real Madrid or Manchester United).

Do not get us wrong, being a great athlete obviously helps. Diego Armando Maradona would have, most probably, scored many more goals and won more silverware, if he had the body and the physical preparation of Cristiano Ronaldo.

However, being a great athlete alone is not enough. Technique and tactical awareness are key to succeed in this sport. While this is widely accepted, the numbers we show here are able to put that into context and make it more evident.

The absence of such correlation is one of the reasons why we are developing a wearable device, for both pro and non-pro footballers, able to capture and analyse the technical performance, on top of the physical and tactical ones. More details about the device in the coming months. Stay tuned.

A series of correlations, all leading to the same result

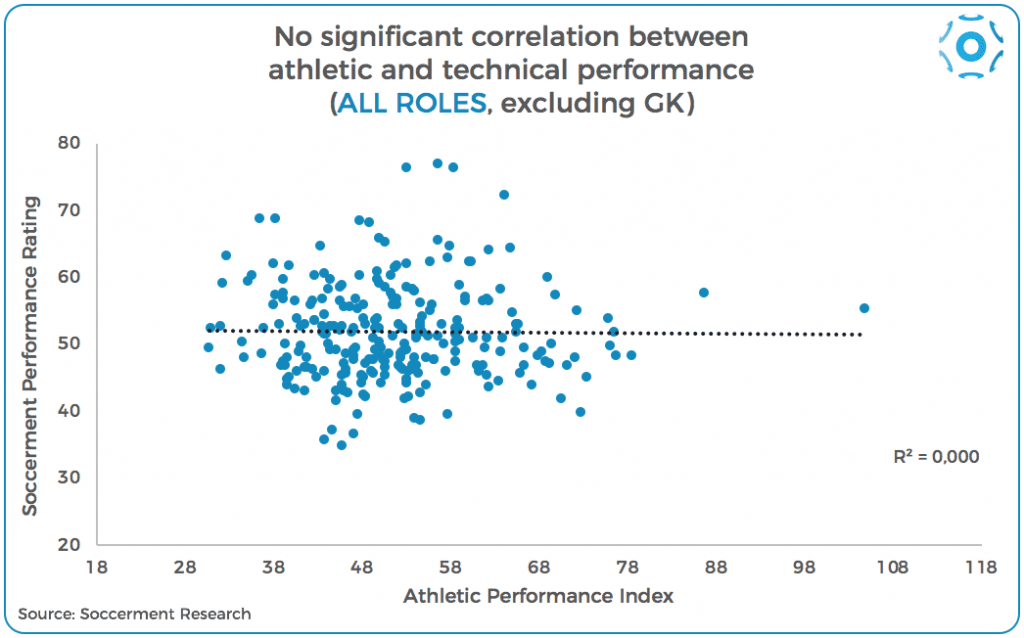

We start with the correlation between the Athletic Performance Index (‘API’) and our Soccerment Performance Rating (‘SPR’), for all the players participating in the World Cup, with the exclusion of goalkeepers.

We calculate the ‘API’ of all the footballers at the World Cup with the stats as provided by FIFA, as we explain in this analysis.

The SPRs provide – in one number – a view of the contribution of a player to his/her team’s defensive, build-up and attacking phases. We briefly explain how the algorithm works in this analysis.

Have a look at the chart below. On the x-axis, there is the API of more than 350 players (we only consider those having played at least 135 minutes). On the y-axis, those players’ SPRs. For consistency purposes, in this analysis we do not use the adjusted version (i.e. adjusted for playing time).

In the chart, there is evidence of the regression line, as well as the related R-squared. As we show, R-squared is 0.000, which tells us that there is no correlation between the two variables.

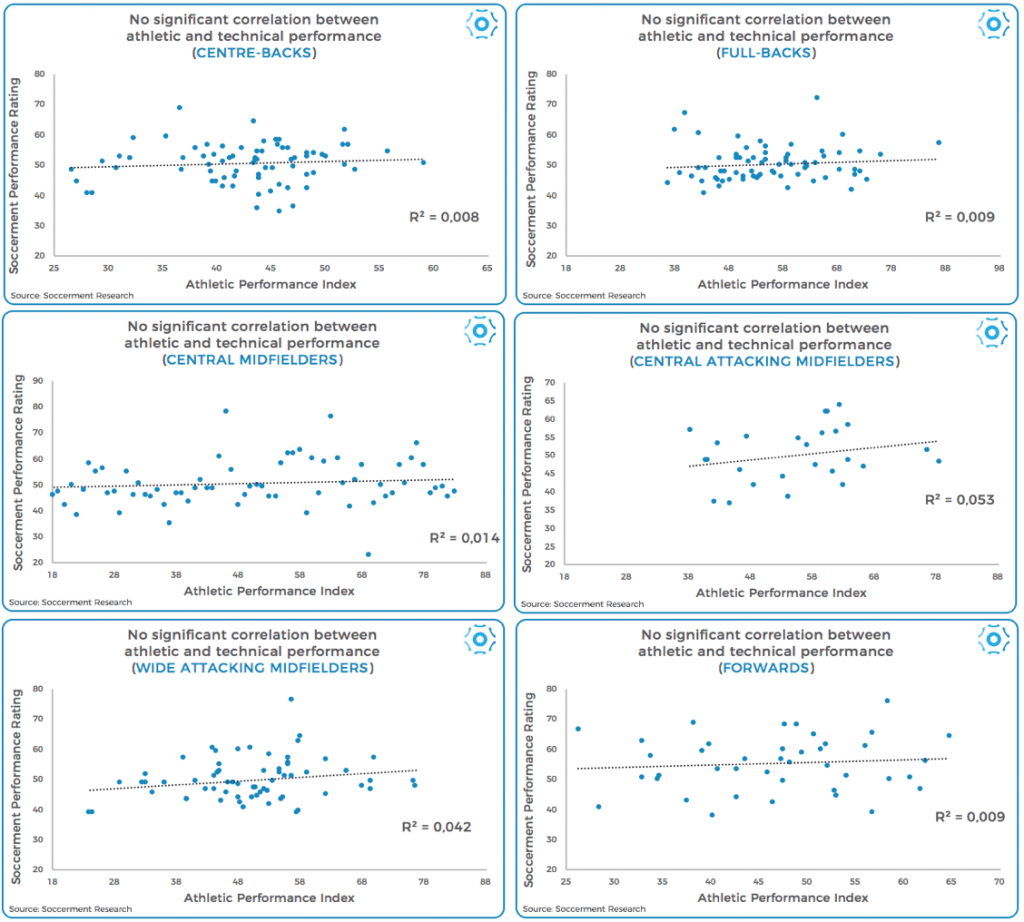

We run it for centre-backs alone. No correlation. For full-backs, R-squared is only slightly higher, but still not enough to have any significance (0.009). The correlation for central midfielders is, again, only 1%. For central attacking midfielders, it is 5%, which is anyway extremely low. On top of this, the sample size is the lowest in this analysis, which makes the relevance of the outcome somewhat weaker. For wide attacking midfielders there is a weak 4% correlation. In the case of forwards, again an R-squared of 0.009 tells us that the correlation between physical and technical performances is virtually 0%.

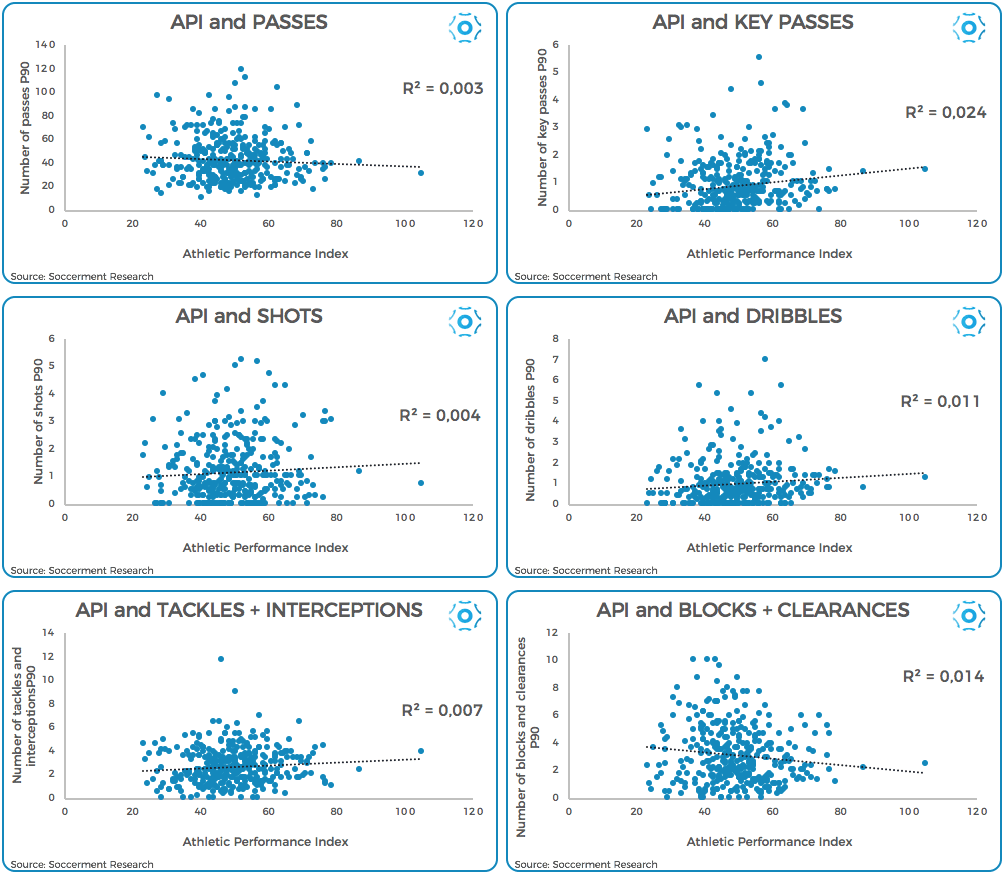

How about the potential correlation of API with the amount of some key events?

We run multiple correlations between APIs and all the events which Opta record, ranging from successful tackles to the number of key passes. From the number of successful headers, to the number of shots and successful dribbles.

Here below, we draw the charts related to the most important ones. There is no event which seems to be ‘really’ positively (or negatively) correlated to the value associated with the physical performances.

How about some selected physical data and associable events? Nope, not even in this case

We leave aside, for a moment, our Athletic Performance Index and we look at specific physical measurements. We focus on the most straightforward, such as the distance covered (in kilometres) and maximum speed (km/h).

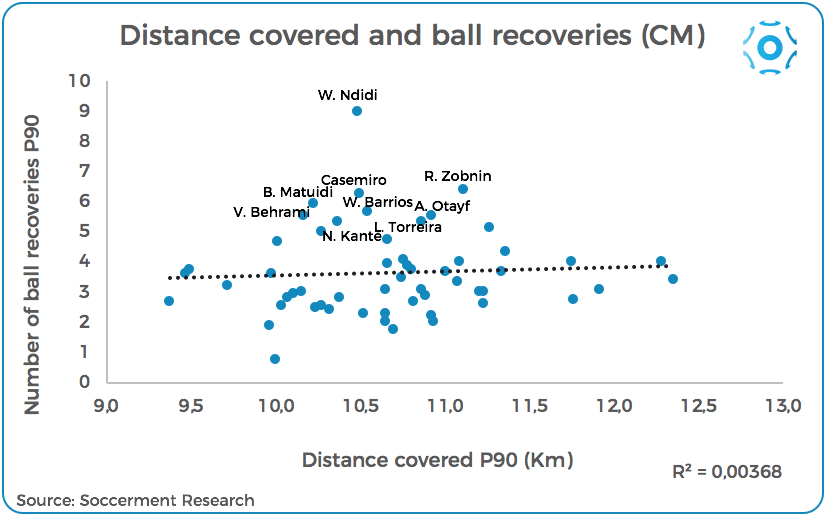

Would Mo Farah recover as many balls as N’Golo Kanté?

We start with the amount of distance covered per 90 minutes. Longer distances are usually associated with tireless midfielders who, thanks to their stamina, are able to recover many balls, through interceptions and tackles. We test it.

The answer is in line with what we have seen so far, i.e. the number of ball recoveries is not significantly correlated with the amount of kilometres you run during the match.

The conclusion we draw is that the ability to run long distances wouldn’t help Mo Farah to be as efficient at ball recoveries as Wilfred Ndidi or the other defensive midfielders who participated in the World Cup.

An effective defensive midfielder displays astute positioning, spatial and tactical awareness, on top of a good amount of stamina.

However, we have to say, Mo Farah has got some skills (see video below).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P4XmKGVVEOU

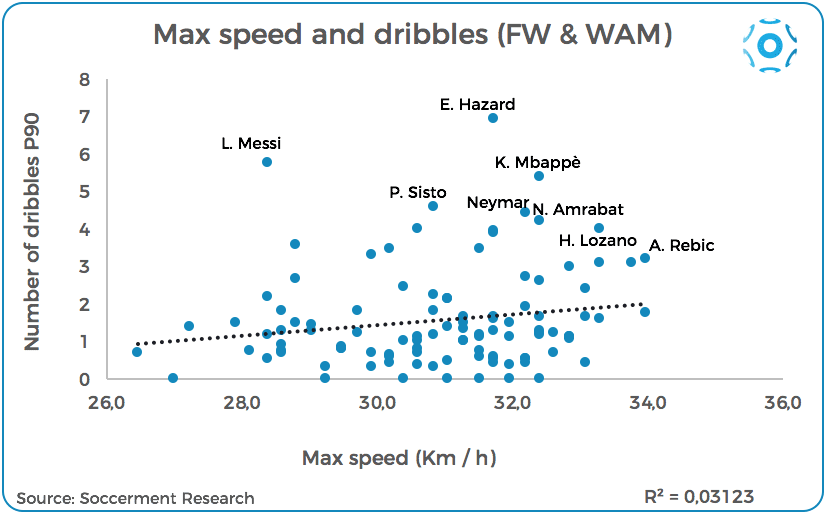

Could Usain Bolt be a great dribbler?

We now look at the recorded maximum speed. We assess whether reaching a higher maximum speed helps at completing more dribbles. If true, this would definitely help Usain Bolt’s case. As a reminder, Usain Bolt reached a maximum speed of 44.72 km/h, during the final 100 meters sprint of the World Championships in Berlin, on 16 August 2009.

The problem is that, however, the analysis of the available data contradicts the popular perception.

We take the data related to the wide attacking midfielders (‘WAM’) and the forwards (‘FW’), who are supposed to be the ones trying to dribble the most and also, as we showed in our analysis, they were the ones sprinting the most at the World Cup (40.9 sprints per 90 minutes for WAM, 37.1 for FW).

The chart below shows quite a loose correlation, with a R-Squared of 0.03. The player dribbling the most at ‘Russia 2018’ was Eden Hazard (6.9 per 90 minutes), who recorded a maximum speed of 31.7 km/h, in the semi-final against France. Ante Rebic, along with Cristiano Ronaldo the fastest player in the competition (34 km/h), dribbled “only” 3.2 times per 90 minutes, on average.

We don’t know what was the maximum speed recorded by Maradona at the 1986 World Cup in Mexico. What we know, however, is that he dribbled 7.6 times per 90 minutes in the competition. Five of the 53 dribbles that Maradona completed in Mexico are in the masterpiece below (GIF).

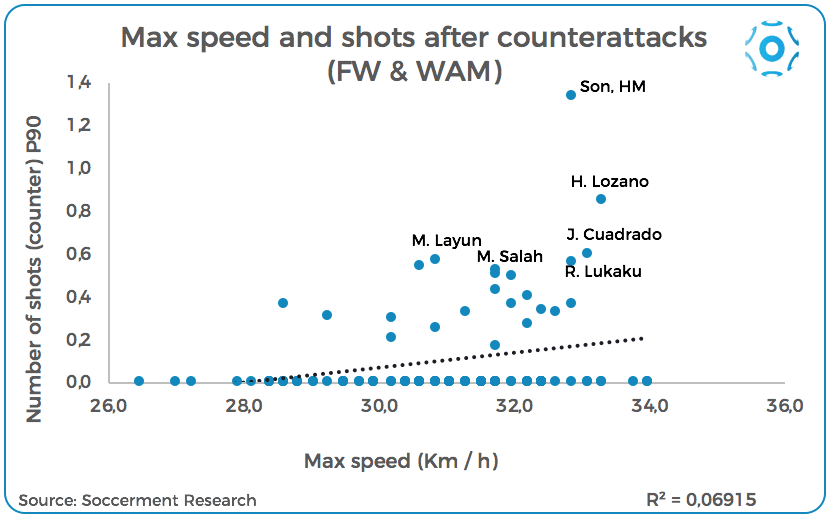

Usain Bolt’s speed would be lethal on counterattacks, right? Well, it depends

Speed is clearly a key features for those attacking players who are willing to exploit counterattack opportunities. We thus stress the potential correlation between the maximum speed – as recorded by FIFA during the World Cup – and the number of shots (per 90 minutes) taken by the players in situations of counterattacks.

The regression between the two variables, at least for the 2018 World Cup, contradicts the common perception, again. R-squared is the highest we have seen in this analysis (7%), but anyway too low to be significant.

By the way, to see Bolt and Farah (12 gold olympic medals between the two of them) playing football against each other, you could have a look at this extract from the Soccer Aid match played in June 2018 (youtube).

Conclusions

Russia 2018 data confirmed that there is no correlation between physical efforts and performances, in line with the available literature. Actually, the absence of any correlation is probably much more striking than the popular perception.

Our findings seem to confirm that a ball-based training is key to master football.

In the past two decades, mainly thanks to the rise of a Barcelona-like approach to training sessions, deriving from the Dutch “totaalvoetbal“, the focus on the ball has greatly increased. Coaches like Pep Guardiola keep stressing about the importance of doing “everything with the ball”, during training. His “teacher”, Johan Cruyff, put most of his attention on the intensity of the training sessions, in particular on the speed of the ball, rather than the speed of the individual players.

As football science evolves and reaches a wider audience, we would expect this focus on ball-based trainings to be adopted by more and more football academies. We believe this will end up improving the quality of the Beautiful Game.

Our research blog will take a little break, but not going on hols

Our research blog will be quiet for a few weeks. We will only remain active on our Twitter page (follow us to remain on top of our analyses).

Not going on holiday, though. We are working hard to bring online our first analytics tool (free of charge and ads-free), for the start of the new season (most likely in mid-September). Before that, however, as a bonus for you and as a test for us, we will bring online a World Cup Beta tool. Owing to popular demand, we are making our entire World Cup database available to everybody. You will be able, inter alia, to compare the players’ data (technical and physical performances), too go through our Soccerment Performance Ratings and Athletic Performance Index. Do not worry about being overwhelmed by big amounts of data, because you won’t. We will make extensive use of intuitive infographics. We really hope you’ll enjoy it. Any feedback will be much appreciated.

Meanwhile, for any comment, query or suggestion, you could send us an email: research@soccerment.com.